Virginia Woolf: England’s Modernist Master

Along with James Joyce and William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf is considered one of the undisputed masters of “stream of consciousness” writing. Born in England in 1882, Woolf’s legacy far outlasted her short life, and her immense oeuvre continues to inspire artists, especially female writers, around the world.

Photograph of Virginia Woolf, via Wikimedia Commons

All of the greatest Virginia Woolf novels challenge how we think about the nature of human perception with their experimental prose and non-linear plots. Her work has also exerted and immense influence on feminist critics and historians who’ve worked hard to uncover an unbiased history of women in the Western world. Although her major works were written in the 1920s, Woolf’s fiction is as fresh today as it was back then.

If you don’t know much about Virginia Woolf, join us as we take a quick look at her incredible life and work.

From Birth to Breakdown: Woolf’s Early Years

Virginia Woolf (née Stephen) was born into a prominent Victorian era family in 1882 in London. Woolf’s biological parents, Sir Leslie Stephen and Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson), were both widowers before they decided to get married in 1878.

Henry H. H. Cameron (1852-1911): Julia Stephen with Virginia on her lap 1884, via Wikimedia Commons

In total, Woolf had seven siblings. Three of her siblings were full-blood and the other four were stepsiblings. Out of all her siblings, Woolf was closest to her full sister Vanessa.

Woolf started writing from a very early age. She was the key writer behind the family’s humorous newspaper Hyde Park Gate News. When not writing, Woolf would often be reading the classics of Western literature in her family’s immense library. She was also exposed to some of the most influential literary minds at the family’s home on 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington. Woolf father was highly respected in the literary world for his Dictionary of National Biography and he had connections to the descendants of author William Makepeace Thackeray through his first marriage.

Sadly, Woolf’s innocent childhood came to an abrupt end in 1895. That’s the year Julia Stephen died. Just as Woolf was recovering from this blow, one of her half sisters died in 1897. Ten years later, Woolf’s father passed away. Woolf’s delicate mind was so shattered by these sudden deaths that she suffered her first nervous breakdown in 1904.

During this time, Vanessa cared for her full brothers and sister. Eventually, all the full siblings moved to the Bloomsbury section of London so they could pursue their artistic pursuits in relative solitude. In case you didn’t know, Vanessa became a celebrated visual artist in her own right, and many of Vanessa’s paintings were placed on the covers of Woolf’s novels.

The Stephens invited numerous public intellectuals to dine with them in Bloomsbury at this time. A few frequent guests to the Stephens’ residence include Colonial Administrator Leonard Woolf, economist John Maynard Keynes, and critic Lytton Strachey. Eventually, this clique of left-leaning intellectuals became known around London as the “Bloomsbury group.”

Woolf Sets Sail into Experimental Fiction: Writing The Voyage Out

After a short trip to Greece, one of Woolf’s full brothers (Thoby) died of typhoid fever at the age of 26. Woolf also lost connection with Vanessa after she became engaged to art critic Clive Bell and moved away. Thankfully, Woolf didn’t suffer a nervous breakdown after these two blows. Instead, she focused her energy on writing and socializing with radical artists and theorists in Bloomsbury.

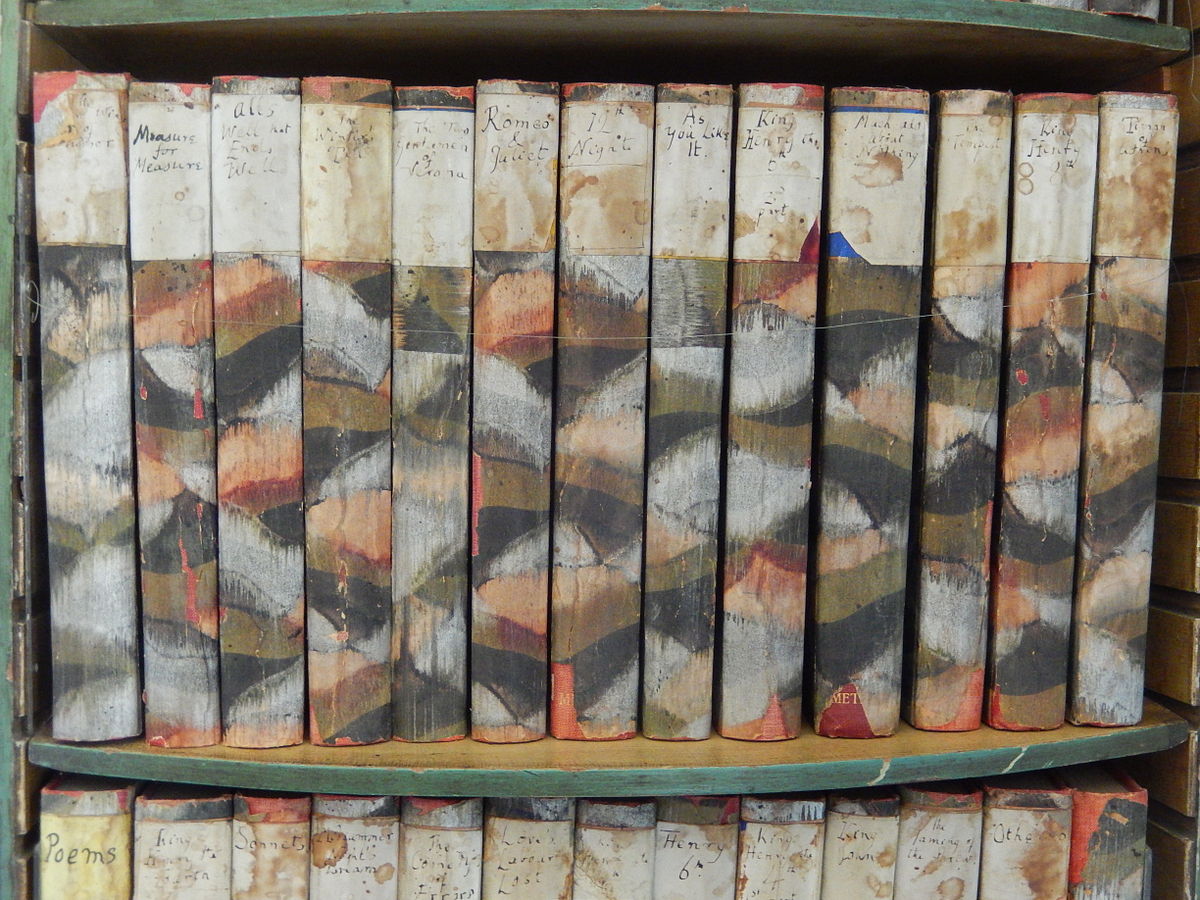

Shelf of Shakespeare Plays Hand-Bound by Virginia Woolf by Ian Alexander, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1908, Virginia Woolf set herself the task of creating a novel that would crystalize the “flight of the mind.” To do this, Woolf believed she had to break with the conventions of traditional Victorian novels.

Woolf began working on a novel called Melymbrosia, but she suffered intense writer’s block. It wasn’t until 1910 that Woolf found the direction she needed for her fictive enterprise. That’s the year a family friend named Roger Fry invited the Stephens to a London art exhibit. This exhibit highlighted the works of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Manet, Picasso, and Cézanne. Woolf saw in these paintings the effect she was hoping to express in her novel.

Woolf decided to change the title of her work from Melymbrosia to The Voyage Out and finally published the work in 1915. This novel follows a woman named Rachel Vinrace who leaves the shelter of London society on an excursion to South America. Interestingly, this novel shows the trajectory of Woolf’s on imaginative project as she attempts to leave the safe confines of Victorian Realism and enter the exotic, but also extremely dangerous, realms of the subconscious mind.

A Literary Marriage, The Hogarth Press, And Woolf’s Early Works

Plaque of the Hogarth Press by Mark Baker, via Wikimedia Commons

While Virginia Woolf was working on The Voyage Out, Leonard Woolf returned to London from a trip to Sri Lanka. Leonard and Virginia were married in 1912 and immediately began work on their literary careers. After quitting his job as a colonial administrator, Leonard started to write a few novels of his own, most of which criticized British colonialism.

Woolf’s manic-depressive episodes started to get progressively worse in 1910. These symptoms got so bad that she actually tried to kill herself in 1913. Woolf was extremely worried about how the public would take A Voyage Out and was saddened by the loss of contact with Vanessa. Later in 1915, Woolf started experiencing strange hallucinations and was on the brink of full-blown psychosis. Luckily, she was able to escape this dark place by 1916.

The “undiscover’d country” of the subconscious mind Woolf attempted to explore in A Voyage Out obviously depleted her of a great deal of psychic energy. To recover from this first voyage into experimental fiction, Woolf decided to return to Realism in her next novel: Night and Day.

Night and Day (1919)

Published in 1919, this novel tells a love story where Ralph (based on Leonard) and Katherine (based on Virginia) have to overcome class and gender prejudices to connect in Victorian England. Anyone who’s intimidated by Woolf’s more experimental works should seriously consider reading the wonderful Night and Day first.

The Woolfs established their own publishing house called Hogarth Press in 1917. In addition to Night and Day, Virginia Woolf published numerous short stories and critical essays that started to gain notoriety. Not only did Hogarth Press publish fiction and non-fiction, it also published many of Vanessa’s illustrations and translations of Freud.

Thanks to the great success of Hogarth Press, the Woolfs were able to buy a house in Sussex called Monk’s House. This allowed Virginia Woolf to visit her sister Vanessa by day and write in solitude in the evening. By the way, anyone visiting the English village Rodmell can tour Monk’s House today.

Monk’s House by Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons

In her next early novel, Jacob’s Room (1919), Woolf attempted to transform her sorrow over the death of Thoby into art. Through a series of loosely connected scenes, readers learn about the life of Jacob as he grows up, goes to college, and eventually dies in World War I. With its strong pacifist message and experimental style, Jacob’s Room established Woolf as a powerful avant-garde writer and paved the way for her major novels

The Productive 20s: Woolf’s Greatest Decade

Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

Literary critics agree that Woolf’s mature career began in 1925 with the publication of Mrs. Dalloway. Taking place on one day in post-WWI London, Mrs. Dalloway reads like an Impressionist painting. Woolf effortlessly blurs the boundaries between the internal and the external world as the socialite Clarissa Dalloway prepares an evening party. The other major character in this novel is WWI veteran Septimus Smith who suffers from shell shock.

Mrs. Dalloway is Woolf’s most famous novel today thanks to the 1997 film adaptation staring Vanessa Redgrave:

To The Lighthouse (1927)

Woolf followed Mrs. Dalloway with another masterpiece: To The Lighthouse. This novel is split into three sections and focuses on the wealthy Ramsay family’s summer trips to their beach house. Woolf heavily drew on her own memories from childhood trips to Talland House in St. Ives while composing To The Lighthouse. This highly symbolic novel deals with weighty issues such the nature of loss, impermanence, and how art can offer solace in the modern world.

“What is the meaning of life? That was all—a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years, the great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one.”

-Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse

Orlando (1928)

In 1928, Woolf published the fascinating Orlando: A Biography. This novel challenges our rigid notions of both gender and genre. The titular poet travels from the English Renaissance right up to the 20th century in this stunning work. Oh, by the way, while he’s voyaging through time, Orlando becomes a she! Without a doubt, Orlandois one of Woolf’s most imaginative novels.

A Room of One’s Own (1929)

One year after the publication of Orlando: A Biography, Woolf published her most famous essay: A Room of One’s Own. This stunning piece explores the many issues female authors have had gaining a foothold in the male-dominated literary world. In the most famous section of this piece, Woolf imagines what would’ve happened if Shakespeare’s sister, whom she calls Judith Shakespeare, had the same talent for writing as her brother during the Renaissance.

The ferocity of Woolf’s prose in A Room of One’s Own has inspired countless readers of both genders ever since its publication. Watch a short review of the seminal work below:

Woolf’s Later Fiction and Death

The Waves (1931)

Woolf’s next great novel is called The Waves. Published in 1931, The Waves is both a profound and difficult text, especially for newcomers to Woolf. The novel follows a group of six friends from their infancy into old age. There are also long interludes where Woolf describes both the sea and the sky. At the end of the novel, it’s hard to tell the difference between the human and the natural world. Some critics even see hints of Hindu mysticism in this work.

The Years (1937)

Most of Woolf’s later career was spent working on a huge text initially titled Pargiters: A Novel-Essay. In this work, Woolf alternated between a fictional family and historical accounts to document the immense changes in English society from the Victorian age to the 1930s. It took Woolf many years of research before she felt confident enough to publish this work. She ended up changing the title to The Years and published it to great acclaim in 1937. The Years was Woolf’s bestselling novel during her lifetime.

Other Works: Flush, Three Guineas, Between the Acts

During this era, Woolf also completed numerous shorter comedic works. One such work, called Flush, is a biographical satire told from the perspective of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog.

One year after publishing The Years, Woolf released a pacifist tract called Three Guineas. This classic work was most likely inspired by the recent death of Vanessa’s son Julian Bell in the Spanish Civil War. In this work, Woolf examines war from a gendered perspective that continues to inspire heated debate.

Portrait of Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford, via Wikimedia Commons

Before her death, Woolf mainly worked on a novel called Between the Acts. This work takes place in a small English town and follows the local gentry as they prepare and perform a show. Readers can almost feel the impending doom of World War II in the background of this story. Despite the threat of war and destruction, Woolf’s final novel is often read as an affirmation of the eternal value of art.

In real life, however, Woolf wasn’t sold on her optimistic message in Between the Acts. As the Luftwaffe bombed London in 1940, Woolf became increasingly depressed about the global situation and about her role as an artist. She also started experiencing terrible hallucinations again. In 1941, Woolf drowned herself in the River Ouse. She was 59.

Between the Acts was published posthumously.

Swimming in Woolf’s Prose

Woolf’s body of work is impressive. Not only did she write spectacular novels, she was also:

- An expert essayist

- Art critic

- Short story writer

- Non-fiction author

Most readers often describe her writing style, especially in her major novels, as “fluid.” Indeed, the symbol of the sea comes up again and again in Woolf’s works. In Woolf’s texts, the reader experiences everything as coursing, moving, and interpenetrating. Woolf seamlessly moves in and out of her character’s minds to give us a radical insight into the interconnectedness of the universe. Sadly, this eternally moving current of consciousness is also linked to Woolf’s untimely death.

Homage to Virginia Woolf (mixed technique) by GEMDIAZ, via Wikimedia Commons

But perhaps Woolf’s death is not a cause for tears. Since Woolf was so fond of breaking binary thought patterns, why shouldn’t we question our own rigid distinction between life and death? Despite all of Woolf’s political writings, her greatest works deal with those eternal questions surrounding birth, aging, and death.

No matter what you read, you’re sure to find deep wisdom, compassion, and beauty in a book by Virginia Woolf.

Leave a Reply

1 Comment on "Virginia Woolf: England’s Modernist Master"

[…] her essay on Russian literature, British author Virginia Woolf wrote […]