The Work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky: “Composed Purely and Wholly of the Stuff of the Soul”

Even in English translation, Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky‘s works pulse with the terror and ecstasy of the human soul. But don’t take our word for it.

In her essay on Russian literature, British author Virginia Woolf wrote this:

“The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in.”

She went on to say that the only author more powerful than Fyodor Dostoyevsky was Shakespeare. While some authors (most notably Vladimir Nabokov) can’t stand Dostoyevsky’s frenzied style of composition, no one can deny his immense influence on 20th and 21st century art and philosophy.

Dostoyevsky’s oeuvre examines both the depths of depravity to which man can sink and the transcendent heights to which he can ascend. The images and insights Dostoyevsky captures in his electric prose will haunt your psyche long after you’ve finished his books.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at Dostoyevsky’s life and work to get you started on your own journey into this master’s mind.

Dostoyevsky’s Early Years And Imprisonment

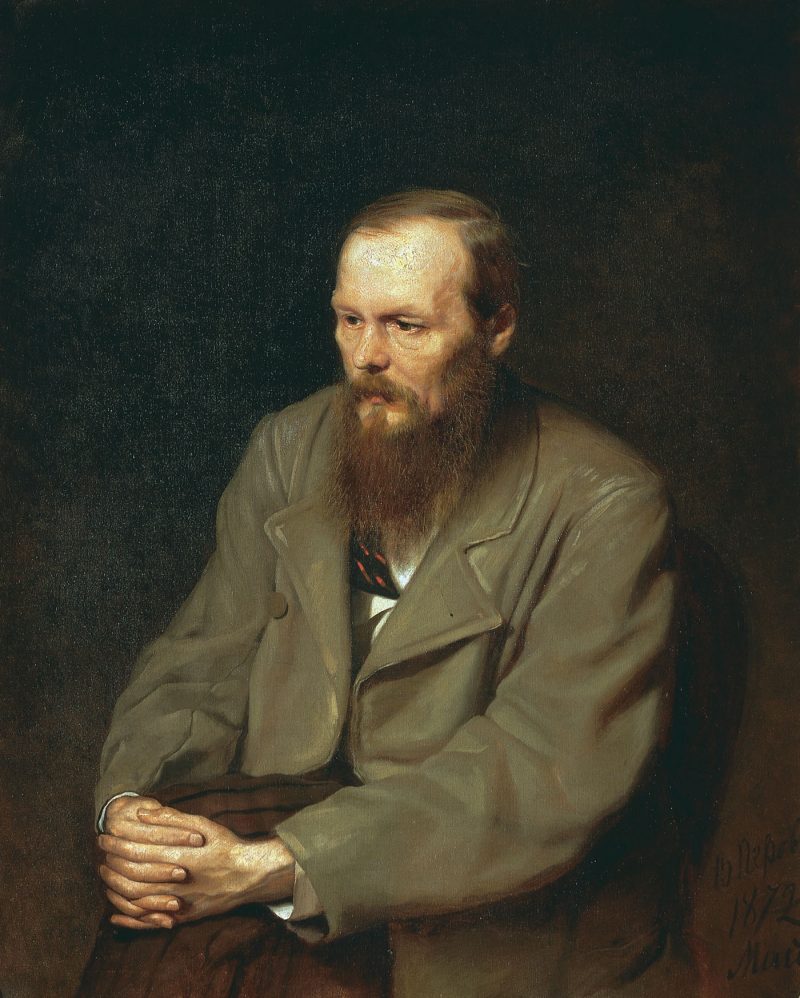

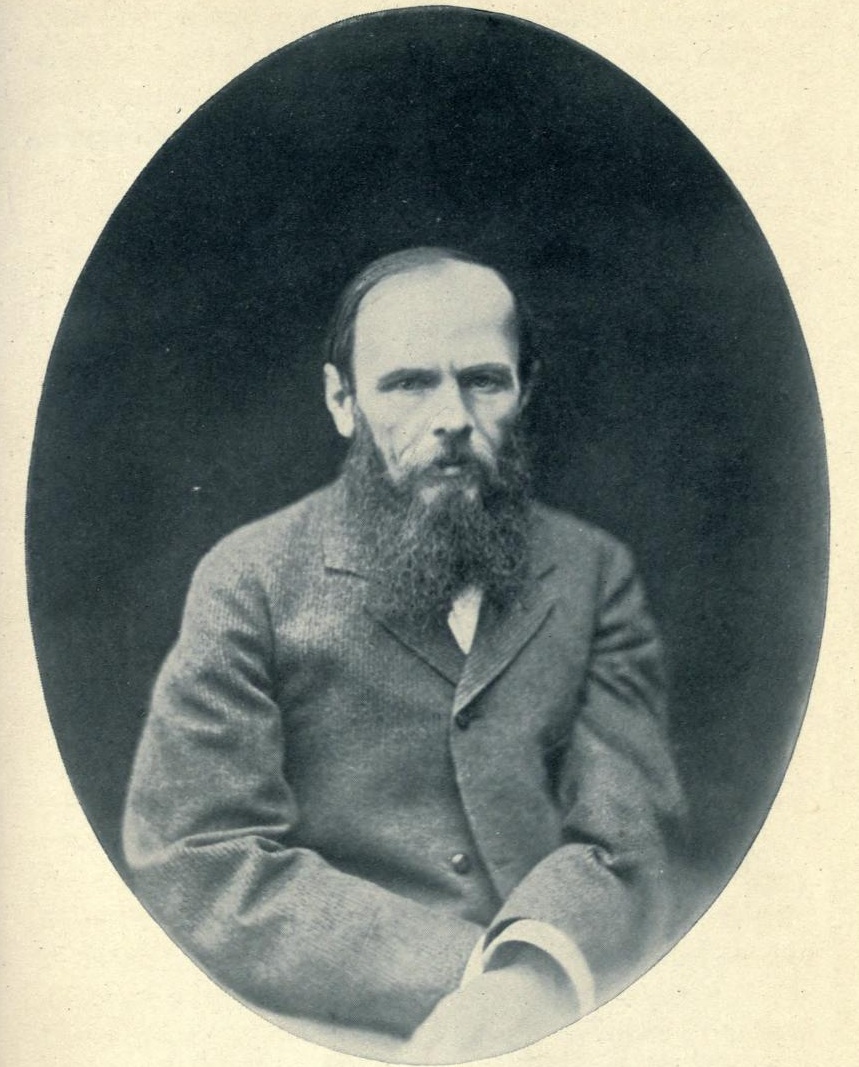

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, via Wikimedia Commons

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky was born in 1821 in Moscow. His father was a doctor and his mother was a deeply pious Russian Orthodox Christian from a merchant family. Critics believe Dostoyevsky’s close proximity to the sick at his father’s hospital influenced aspects of his later fiction, most of which focuses on marginalized segments of Russian society.

In 1837, Dostoyevsky’s mother suddenly died. He lost his father just two years later. At that time, Dostoyevsky was studying to become a military engineer at the Academy of Military Engineering in St. Petersburg. Despite the promise of a stable career, Dostoyevsky never wanted to become an engineer. The young Fyodor fell under the spell of fiction from an early age. Although Dostoyevsky earned enough credits to become a sub lieutenant, he decided to try his luck as a writer.

A few of Dostoyevsky’s favorite authors at this time were:

- Sir Walter Scott

- Charles Dickens

- Aleksandr Pushkin

- Honoré de Balzac

Dostoyevsky’s First Novel: Poor Folk

Amazingly, Dostoyevsky met with instant success after the publication of his first novel: Poor Folk. While this epistolary novel about a poor copying clerk isn’t studied much today, it already shows Dostoyevsky’s interest in psychological realism. Dostoyevsky, who was hailed as a “new Gogol” by St. Petersburg critics, often said that this was the happiest moment of his life.

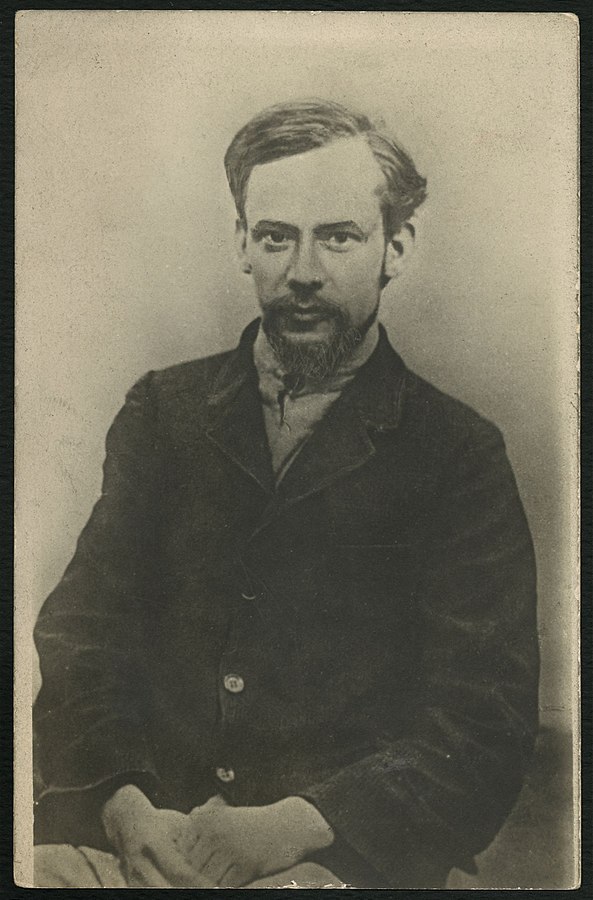

Fyodor Mikahailovich Dostoyevsky’s Study in St. Petersburg, via Wikimedia Commons

While Dostoyevsky gained entrance into St. Petersburg’s intelligencia, he instantly ruffled feathers with other writers. In particular, Fathers and Sons author Ivan Turgenev was turned off by Dostoyevsky’s temperament. Unfortunately, Dostoyevsky’s second novel about a schizophrenic, which he called The Double, didn’t do nearly as well as Poor Folk. Dostoyevsky’s continued focus on individual psychology rather than societal issues didn’t endear him to the more radical segments of the St. Petersburg literati.

It was also during this time that Dostoyevsky became more active in politics. He joined a group called the Petrashevsky Circle in 1847.

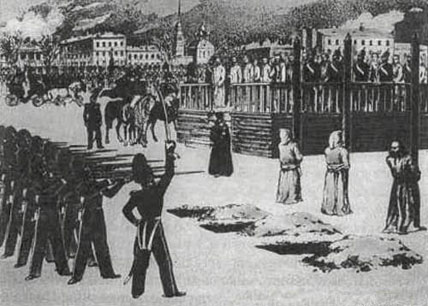

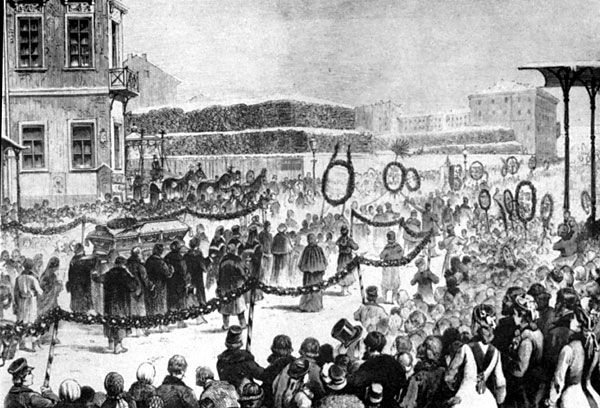

Petrashevsky Circle members in a mock execution in St. Petersburg, by B. Pokrovsky (1849), via Wikimedia Commons

While this group was interested in socialist ideas, Dostoyevsky mainly joined because he was a staunch opponent of serfdom. Dostoyevsky’s involvement with this group led to his arrest in 1849. He was sentenced to be shot by a firing squad at Semyonovsky Square in December. Just before the officers pulled their triggers, Tsar Nicholas I removed the death penalty. Dostoyevsky was reassigned to serve his prison sentence in a Siberian work camp.

Russia’s First Great Prison Memoir: House of the Dead

As you could imagine, Dostoyevsky’s experiences in prison deeply affected his mind. To compound his already immense difficulties, Dostoyevsky started to develop epilepsy in prison, a disease that would plague him for the rest of his life.

All of these trials, however, served as inspiration for Dostoyevsky’s faith in the Russian Orthodox Church. He famously wrote these words in his diary:

“If someone proved to me that Christ is outside the truth, and that in reality the truth were outside of Christ, then I should prefer to remain with Christ rather than with the truth.”

When he was allowed to return to Russia ten years later, Dostoyevsky married a widow named Mariya Dmitriyevna Isayeva. Sadly, Isayeva died of tuberculosis only seven years into the marriage.

To earn a living, Dostoyevsky immediately began writing down stories from his time in Siberia. This eventually became the powerful memoir House of the Dead, which we discussed previously in our post about five impactful books about prison.

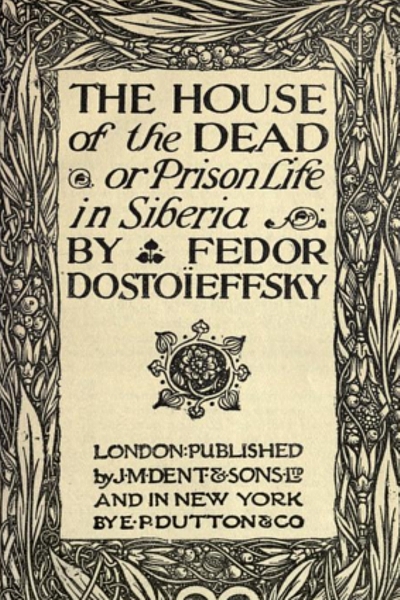

The House of Dead by Fiodor Dostoyevsky, book cover, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1911, by AngelSanz1977 (own work), via Wikimedia Commons

In this vivid text, Dostoyevsky describes both the horrors of his criminal companions and the sadism of the prison guards. Despite these atrocities, Dostoyevsky insists that no form of social engineering can help criminals. Instead, Dostoyevsky insists on personal freedom and humanity’s natural goodness, a conviction that put him at odds with the socialists of his day.

Indeed, Dostoyevsky’s insistence on liberty over social engineering made him one of the Bolsheviks’ least favorite writers.

Dostoyevsky’s Breakthrough: Notes from the Underground (1864)

Almost all literary critics agree that Dostoyevsky’s novella Notes from the Underground marks the beginning of the author’s mature fiction.

Notes from Underground cover, via Wikimedia Commons

Published in 1864, this novella is split into two sections and is narrated by a “spiteful” unnamed narrator. The first section is a direct attack on the idealism of Russian utopians, especially Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky. Dostoyevsky’s narrator argues that even if a “perfect” society could be created, humans wouldn’t accept it. Why? Because such a system denies free will and irrationality.

In the second section of this novella, Dostoyevsky relates a story from the narrator’s past. In this short story, the narrator meets a group of friends for dinner and gets into a nasty row. Later on, he becomes entangled to a prostitute named Liza. This second section illustrates the narrator’s previous insights into the irrationality of man in story form.

If you’re just beginning to read Dostoyevsky, this is the book to start off with. In addition to being an engaging read in its own right, Notes from the Underground clearly lays out all the major themes that come up again and again in Dostoyevsky’s later novels.

Dostoyevsky’s Great Novels of 1860s

At the start of the 1860s, Dostoyevsky took an extended trip to Western Europe. His reason for doing so was twofold. First, he wanted to observe how Westerners differed from Russians. Second, and perhaps more importantly, he wanted to escape his debts. Dostoyevsky was a compulsive gambler, and he racked up astronomical debts in his homeland.

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1872), via Wikimedia Commons

The Gambler (1866)

Luckily for Dostoyevsky, he soon met Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina. Snitkina worked as Dostoyevsky’s stenographer as he dictated his next novel: The Gambler.

This novel, about the tutor/gambling addict Alexey Ivanovitch, was directly based on Dostoyevsky’s own addictions. In 1867, a year after The Gambler was published, Dostoyevsky and Snitkina were married. Snitkina worked hard to straighten out Dostoyevsky’s finances so he had a better environment in which to work. The couple had four children, but only two grew up into adulthood.

Crime and Punishment (1866)

Dostoyevsky’s next great novel, Crime and Punishment, is his most widely studied work.

Crime and Punishment cover, first edition, via Wikimedia Commons

The bulk of this novel is set in St. Petersburg during a sweltering summer. Raskolnikov, the novel’s protagonist, is a poor student enflamed by ideas of moral relativism from the West. Believing he’s a “superior man,” Raskolnikov murders two women in cold blood. Throughout the rest of this novel, Dostoyevsky analyzes the numerous conflicting motivations floating around Raskolnikov’s mind. This novel is also well known for characters like the sensualist Svidrigailov and Detective Porfiry Petrovich.

The Idiot (1869)

Dostoyevsky followed Crime and Punishment with another great novel: The Idiot. Published in 1869, this novel centers on the epileptic Prince Myshkin (the “idiot”) whose good nature only gets him into deep trouble. The novel almost reads like an elaborate Russian soap opera, full of love triangles, greed, deception, and even a suicide attempt.

Dostoyevsky’s Late Masterpieces

Just when the world thought Dostoyevsky was done ticking off the radicals, he showed that he still had more up his sleeve.

The Possessed (1872)

The Possessed (also called The Demons) was published in 1872. Many readers see The Possessed as a prophetic novel, especially the novel’s second plot about a group of violent utopian revolutionaries. Even today, The Possessed is championed as a brilliant work of political psychology.

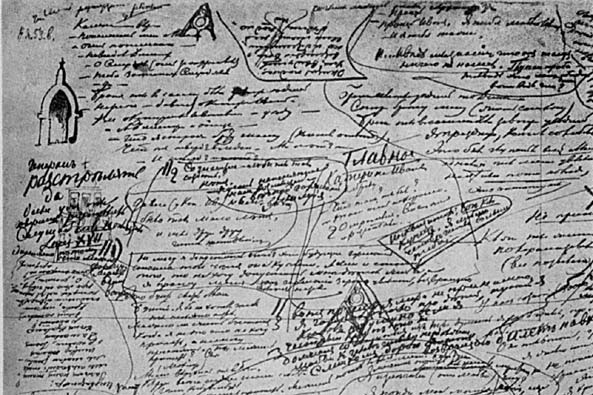

Paragraph from The Brothers Karamazov (Russian), via Wikimedia Commons

The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

Dostoyevsky’s final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, is easily one of the top five novels ever written. Although ostensibly a crime novel, The Brothers Karamazov reads more like a long meditation on the greatest themes in all of literature: the meaning of life, the nature of God, free will versus determinism, and the eternal struggle between good and evil.

Dostoyevsky’s notes for Chapter 5 of The Brothers Karamazov, via Wikimedia Commons

All three of the Karamazov brothers approach life in different ways with varying results. Dmitry, the eldest, is a sensualist. Ivan, the middle child, is an atheistic intellectual. The youngest son, Alyosha, is a monk. The plot of this novel focuses on the murder of the boys’ tyrannical father, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov. But the murder isn’t really the issue in this piece. Like all great works of fiction, Dostoyevsky is concerned with the quest for the supreme truth about life and death.

The most famous part of this novel is a short section called “The Grand Inquisitor.” Many college students just read this chapter as a standalone piece. In it, Ivan imagines what would happen if Christ returned to earth during the Grand Inquisition. Dostoyevsky hoped to provide the greatest arguments against God in this chapter only so he could disprove them with the rest of the novel.

Dostoyevsky died of a hemorrhage one year after publishing The Brothers Karamazov in St. Petersburg. He was 59 years old.

Dostoyevsky’s Funeral by V. Porfiryev, via Wikimedia Commons

Dostoyevsky: Voice Of The Russian Soul

In all of his fiction, Dostoyevsky was more interested in the complexities of the individual soul rather than the fashionable “-isms” of his day. Dostoyevsky was a man who valued faith and individual liberty and who clearly understood the irrational side of man’s psyche. The psychological insight in Dostoyevsky’s works profoundly influenced the course of 20th century philosophy, psychology, and theology.

Fyodor Mikahailovich Dostoyevsky (1880), via Wikimedia Commons

In fact, Dostoyevsky’s influence is still strong on many major thinkers in our own day and age. For example, In the World Interior of Capital by German theorist Peter Sloterdijk examines globalism using Dostoyevsky’s observations of Western Europe.

In The Decline of the West, German historian Oswald Spengler wrote that Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy are the heart and soul of Russian literature. While Tolstoy’s great novels spoke for the more Westernized aspects of Russian culture, Dostoyevsky wrote of the Russian peasantry and the native soul.

If you’ve never read a Dostoyevsky novel before, prepare yourself for the most intense reading experience of your life.

Leave a Reply

2 Comments on "The Work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky: “Composed Purely and Wholly of the Stuff of the Soul”"

Such a wonderful read. Thank you!!

Glad you enjoyed the article, Sanheeta!