From Confucius to the Communists: Five of the Best Chinese Writers

No other civilization in the world has endured as long as the Chinese. Despite wars, famines, revolutions, and imperialism, the Chinese have been able to retain their language and cultural heritage for some 5,000 years.

With China’s rapid economic development in the 21st century, it’s clear that this nation will be a major player in global politics for the years to come. And one of the best ways for outsiders to dip into the mind of the Middle Kingdom is to take a look at the nation’s best writers.

Of course, it’d take a few pretty thick books just to list all of the achievements in Chinese literature over the centuries…

So in this short article, we’ll detail just 5 of the key intellectuals, poets, and novelists that have exerted a strong influence on the Chinese psyche and the course of world literature.

Five Great Chinese Authors

Confucius

What is China without Confucius (Chinese: 孔子)? Indeed, what is East Asia without Confucius?

The only other person that influences Asian culture as strongly as Confucius is the Buddha. But even that’s debatable. Although Mao Zedong tried to erase Confucius from China’s collective memory through the brutal Cultural Revolution, The Little Red Book has yet to displace the Analects in the hearts of billions of Chinese citizens.

Portrait of Confucius, via Wikimedia Commons

So, who was Confucius and what makes him so important? Well, most scholars believe Confucius was born in 551 BC in Shandong province. Confucius’s family was extremely poor and his father died when he was young. Despite his hardships, Confucius became a scholar thanks to his voracious reading. He began working in the local government in his late teens and got married at the age of 19. During this time, Confucius continued to study the classical arts, which included music, calligraphy, archery, poetry, and history.

By the time he reached his mid-30s, Confucius was a well-respected teacher. Not only was Confucius interested in transmitting knowledge, he believed that public education could help transform people and society for the better. His belief in education was so strong that it led to the eventual establishment of the Imperial Examination system. For Confucius, it was integral for scholars to share their knowledge with the public to create a positive ripple effect throughout the nation.

Confucius among his pupils, via Wikimedia Commons

Although Confucius briefly worked as a minister of justice in his home state of Lu (present-day Qufu), he became greatly distressed by the avaricious politicians surrounding him. At the age of 56, he decided to live in exile for 12 years with a group of dedicated students. It was during this time that many of his famous sayings were written down in texts like the Analects (Chinese: 論語).

Over the centuries, the Analects has become the most important of the “Four Books” of Confucianism. This text, which takes the form of a dialogue between Confucius and his students, lays out the key ideas that inform Asian society to this day: respect for elders, reverence for rituals, and the belief that a well-rounded education makes a student virtuous.

Here are just a few gems from this wise text:

- “To be wealthy and honored in an unjust society is a disgrace.”

- “Not yet understanding life, how could you understand death?”

- “To be poor without feeling ill will is much more difficult than to be wealthy without being arrogant.”

At the end of his life, Confucius returned to Lu to spread his ideas on education and virtue. He died in 479 BC and was buried in Qufu. Millions of devoted followers make a pilgrimage to this cemetery grounds every single year.

Photograph of Tomb of Confucius, by Rolf Müller, via Wikimedia Commons

Telling the story of China without Confucius is like telling the story of the West without Socrates. This wise man’s works continue to inspire educators, families, in China, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. In addition to the Analects, other great works attributed to Confucius include the Book of Odes and the Book of Documents.

Lao Tzu

There’s a great deal of debate whether the teacher known as Lao Tzu (Chinese: 老子) actually existed. Like Homer in the Western Canon, most of the stories about this writer’s life are shrouded in mystery. Some scholars believe Tzu was an older contemporary of Confucius, while others say “Lao Tzu” was just a name used by a group of writers.

Statue of Lao Tzu by 氤氲小调, via Wikimedia Commons

Legend has it that Tzu, who had been an archive keeper at the imperial court, left his job at the age of eighty. As he was about to pass the border from China in to Tibet, a guard requested that the master record his philosophy on life before passing through. The result of that exchange is the 5,000 character mystical poem we still have today: the Tao Te Ching (Chinese: 道德經).

The Tao or Dao (道) can be roughly translated as the “way” or the “path.” The Tao Te Ching expresses a philosophy of non-action and non-interference into the natural flow of life. Tzu suggests that when humans stop trying to arrange nature to our own specifications, they attain to the peace and sublimity of the Tao. Some believe this work is all hokum, while others base their whole lives around it. The Tao Te Ching remains the first and central text of the Chinese religion called Taoism.

Both the philosophy in this text and the mystical story of Tzu’s departure from China are diametrically opposed to the Confucian ideal of the “engaged citizen.” But instead of seeing Tzu and Confucius as opposites, perhaps it’s best to see them as necessary compliments…or, as the Chinese might see it, they form a natural yin and yang.

The Tao Te Ching has exerted a profound effect on the history of Chinese religion and spirituality. Chan Buddhism, for example, was a combination of traditional Buddhist teachings and Taoist spirituality beginning in the Tang Dynasty. Today, millions of people from all different faiths have been inspired by Tzu’s witty, wise, and beautiful verses.

Here are a few verses that just might inspire you:

- “To understand the limitation of things, desire them.”

- “Trying to understand is like straining through muddy water. Have the patience to wait! Be still and allow the mud to settle.”

- “Success is as dangerous as failure. Hope is as hollow as fear.”

Li Bai

The Tang Dynasty, which lasted between 618 and 907 AD, is still considered a golden age in Chinese literary history. During this time, China produced its two greatest poets: Li Bai (Chinese: 李白) and Du Fu. If you’re interested, you can read more about Du Fu in one of our previous posts.

Li Bai was born in a city near Chengdu in 701 AD. When he turned 24, he decided to take up the life of a wandering poet. He married a woman named Anlu in Hubei province and made money by writing poetry for court officials.

In 742, he finally arrived in Xi’an, the capital of Tang China. By 756, he became a poet to one of the emperor’s sons. Unfortunately, this naughty son was plotting to overthrow his father, so Li Bai was imprisoned for his connection to the prince. After he was released from prison, he wandered around eastern China and probably died at a relative’s house in 762 AD.

Painting of the Drunken Li Taibai, painted by Qing dynasty painter Su Liupeng, via Wikimedia Commons

Li Bai was a great lover of wine, women, and song. His verses are concerned with romantic themes like impermanence, immortality, drunkenness, and the sublimity of nature. Many readers were so enchanted by Li Bai’s verses that a rumor started to spread surrounding his death. So the legend goes, a drunken Li Bai died trying to capture the moon’s reflection in the water. Although there’s no truth to the story, most Chinese actually believe this is how their great Tang era poet died.

One of the most famous verses in all of Chinese poetry is Li Bai’s “Thoughts on a Still Night.” Bai wrote this poem when he was on a government assignment far away from his hometown. This short verse remains one of the most profound poetic expressions of homesickness in any language:

Before my bed, the moon is shining bright,

I think that it is frost upon the ground.

I raise my head and look at the bright moon,

I lower my head and think of home.You can watch a beautiful musical rendition of this poem here:

Cao Xueqin

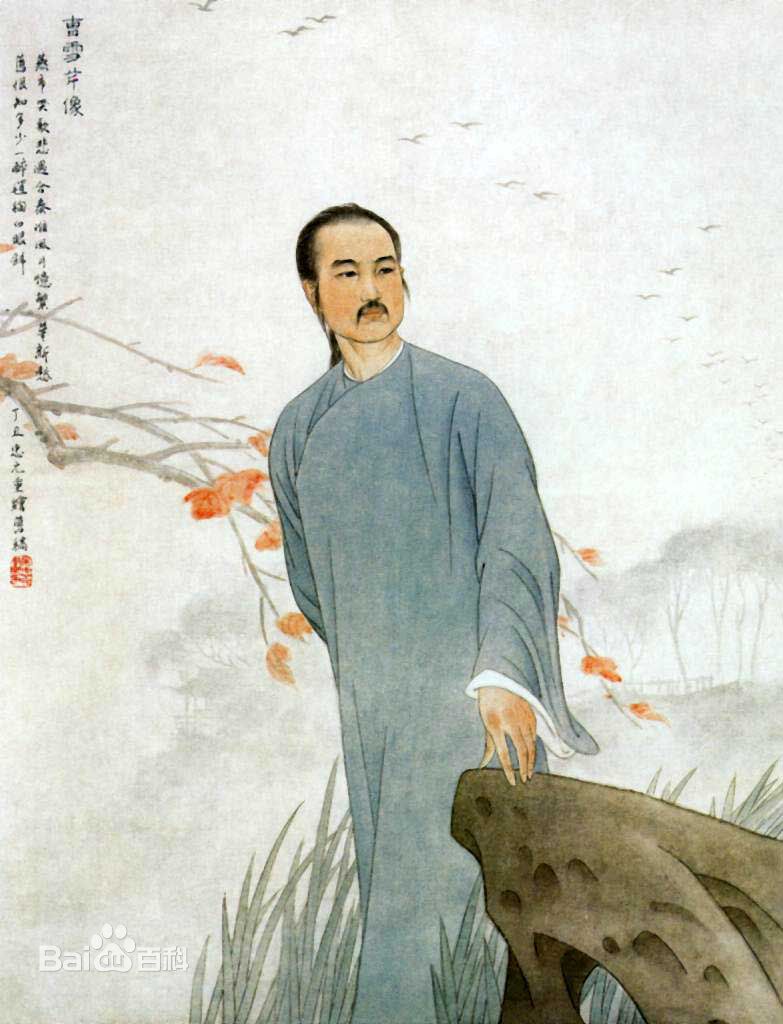

The most recent of China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” is a work called The Dream of the Red Chamber by a man named Cao Xueqin (Chinese: 夢阮).

Cao Xueqin, by Mankong, via Wikimedia Commons

As with the authors of the other four classic novels, not much is known for sure about Xueqin’s life. Historians believe he was born into a wealthy family in Nanjing around 1715. Xueqin’s affluent childhood was shattered once the Yongzheng Emperor took the throne in 1722 and started confiscating the Xueqin family’s property. The exact reasons why the Emperor took such drastic measures isn’t known, but most believe it had something to do with political disagreements. Xueqin and the rest of his family instantly went from riches to rags and were forced to moved to Beijing in search of employment.

Nobody knows for certain what Xueqin did while he was in Beijing. Many critics believe he worked odd jobs, frequented taverns, and worked on his semi-autobiographical novel in his spare time. Xueqin eventually ended up in the countryside and made most of his money selling paintings. He had a wife and one son, and he probably died in 1764 due to complications from alcohol abuse.

Statue of Cao Xueqin, via Wikimedia Commons

Xueqin didn’t complete or publish his novel The Dream of the Red Chamber during his lifetime. Professors believe Xueqin wrote at least 80 chapters in this epic work and a few of his friends wrote the rest before publication in 1791. Sometimes described as “China’s Romeo and Juliet,” The Dream of the Red Chamber tells the story of two families (the Rongguo House and the Ningguo House) in the Jia clan during the Qing Dynasty. Xueqin obviously drew from his own family’s rise and fall in this intricately detailed tale.

The novel’s protagonist is a boy named Jia Baoyu who falls in love with his cousin Lin Daiyu. The main conflict is that Baoyu is supposed to marry another woman named Xue Baochai. With this romantic entanglement in the foreground, Xueqin details the inevitable collapse of the Qin Dynasty.

This novel became incredibly famous both in China and Japan during the 18th and 19th centuries. Believe it or not, there’s even a field of study called Redology dedicated to the study of this novel. Due to the novel’s relative proximity to our own time and Xueqin’s use of Chinese vernacular, Dream of the Red Chamber is considered the most easily accessible of the “Four Classic Novels.”

Lu Xun

If you want to get a better understanding of 20th century China, Lu Xun (Chinese: 魯迅) is the author for you.

Photo of Lu Xun, via Wikimedia Commons

Born in 1881 into a prominent family in Shaoxing, Xun’s grandfather was incarcerated in 1893 for fraud and his family faced harsh criticism from the community. Xun’s family moved to Nanjing in 1899 where he formally studied mining and became interested in Charles Darwin’s works. In 1902, Xun was able to travel to Japan to study medicine. While in Japan, Xun started writing for radical magazines that supported Chinese revolutionaries. He was also forced into an arranged marriage around this time.

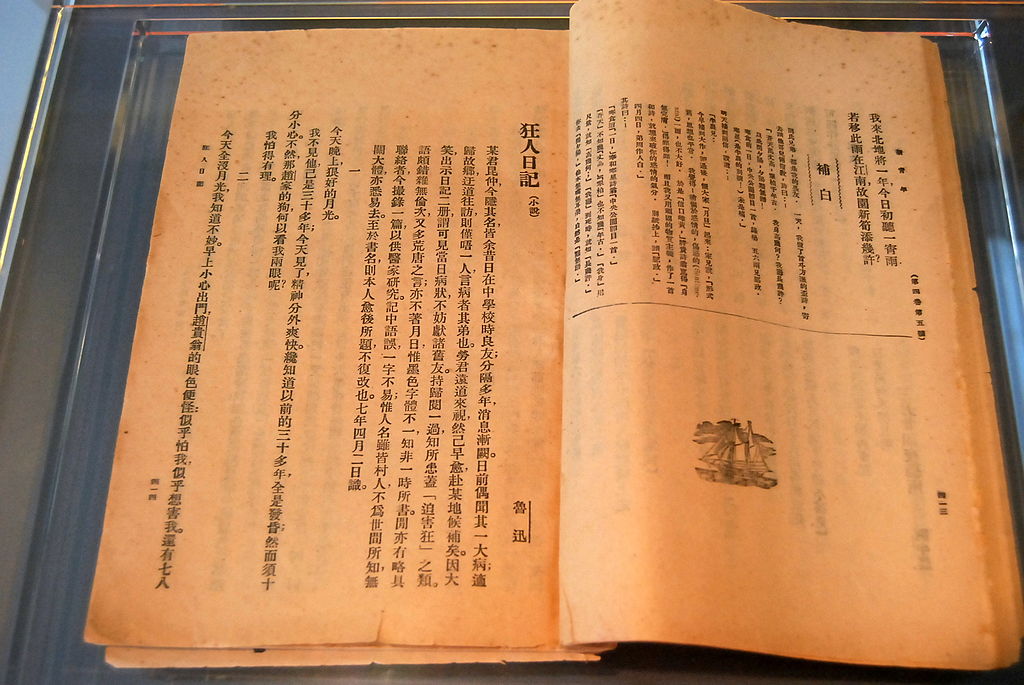

After returning to China, Xun landed a job in the government in Beijing. He published his first major short story, “Diary of a Madman” in 1918. Inspired by Nikolay Gogol‘s story with the same title, is a harsh critique of Confucian values. Xun followed this story up with the short novel The True Story of Ah Q, which also attacked old Chinese customs.

A Madman’s Diary, published in the La Jeunesse (New Youth) magazine Volume 4, Issue 5, via Wikimedia Commons

These two stories made Xun incredibly famous among the Chinese literati. He instantly got jobs teaching at some of Beijing’s most prominent colleges. During this time, he used the resources at Beijing’s universities to complete his comprehensive Brief History of Chinese Fiction. He also translated numerous texts from Russian literature into Mandarin.

In 1926, Xun decided to leave Beijing and settle in Shanghai. While in Shanghai, Xun worked on political essays and joined the League of Left-Wing Writers. He began supporting the Communist Party because he thought they were the best hope for China’s future. He also had an affair with a former student at this time.

Some of the best works from Xun’s later life include his prose-poems and his political essays expressing his uniquely pessimistic attitude towards Chinese politics. He died in 1936 in Shanghai and was celebrated as an exemplar of Socialist Realism by Chairman Mao. Many Chinese schoolchildren in the 1950s were forced to read Xun’s poems, prose, and letters in school. People can now visit both a park and museum in Shanghai dedicated in Xu’s honor.

Lu Xun Memorial, via Wikimedia Commons

A Final Tip for Westerners: Start With Ezra Pound

Of course, you could just plunge into any one of these texts above. However, sometimes the cultural barriers can stifle our aesthetic enjoyment of these texts.

One interesting way to overcome this dilemma is to pick up a few works by American poet Ezra Pound. As most literature buffs already know, Pound was a huge admirer of Chinese language and literature. Believe it or not, Pound actually hid a Confucian text in his pocket as he was being led to an Italian prison.

Title page from Ezra Pound, Cathay, London, Elkin Mathews, 1915, via Wikimedia Commons

Fellow Modernist poet T. S. Eliot noted that, “Pound is the inventor of Chinese poetry” for the 20th century. Although Pound’s translations of Chinese poems aren’t accurate in the scholarly sense, his renditions of poems are as close as we can get to the feel of Chinese poetry. Anyone seriously interested in Chinese literature should consider reading through Pound’s Cathay or his 13th Canto a few times.

Although it’s not authentic, there’s still no greater bridge between the Chinese and the Western mind than Pound’s vibrant Modernist translations.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!