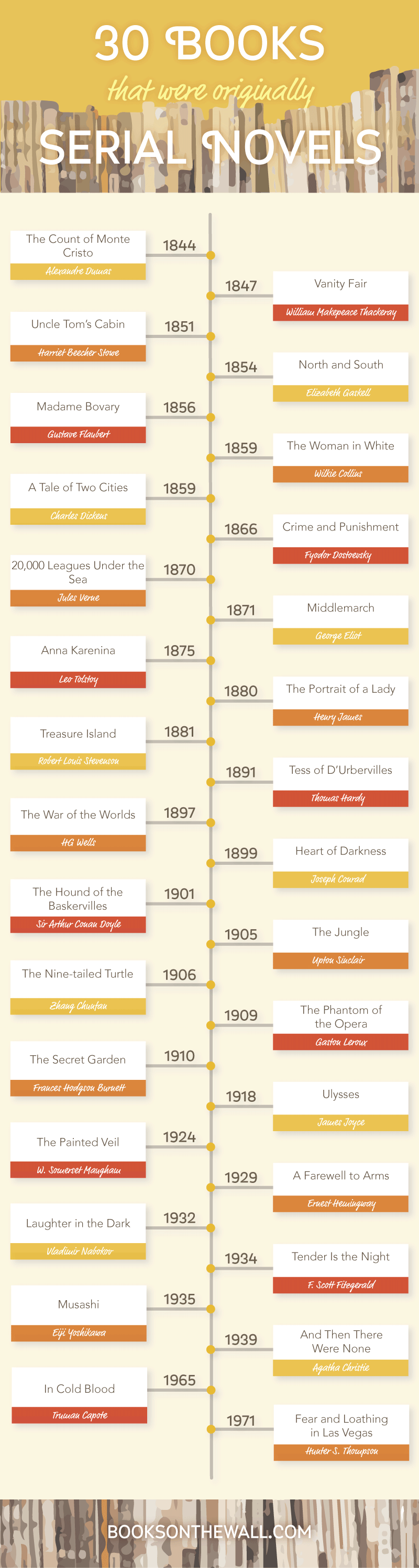

The Serial Novel: A Brief History [Infographic]

What is a serial novel?

A serial novel is a work of fiction that is published in sequential pieces called installments. These installments can be published at nearly any interval for nearly any period of time, though weekly and monthly installments are most typical. Serialized novels have traditionally been published by literary magazines, newspapers, and other periodicals.

In fact, the breakout hit podcast Serial got its name from this style of publishing a story in installments.

Some serial novels—like The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins—were written specifically for that format, while others—like parts of Middlemarch by George Eliot—were originally intended to be a longer work but were later broken up for serialization. (Eliot actually did not want to serialize Middlemarch, but her work was simply too long for a standard three-volume publication. You can read more about the development of the novel’s unique serialization here.)

In the 1800s and early to mid-1900s, serialization was an immensely popular form of publishing. Publishing works in serialized form gave authors a much wider readership since even poorer readers could afford short volumes. Publishers of course enjoyed the corresponding greater profits.

After first publishing in serial format, many authors would revise the work before publishing it to be sold as a complete novel.

History of serialized publishing

Even though serial publishing had existed long before, Charles Dickens is often credited with beginning the serial publishing craze with The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (more frequently called The Pickwick Papers). The Pickwick Papers were published over 19 issues from March 1836 to October 1837.

Charles Dickens wrote most of The Pickwick Papers under his pseudonym Boz, a name he had used to much success with an earlier serial work, Sketches by Boz.

The Pickwick Papers follows an elderly gentlemen named Samuel Pickwick as he journeys around the British countryside. In this work, Dickens established his now-iconic humorous voice, exaggerated characters, and piercing gaze into the various foibles of Victorian English society.

You can read the whole text of The Pickwick Papers for free on Project Gutenberg, one of our favorite literary websites.

Photo: Public domain, Wikicommons

Dickens did not stop writing serial fiction after the success of Sketches by Boz and The Pickwick Papers. In fact, Charles Dickens published all of his novels, including Great Expectations and Little Dorrit, in serial form first.

He went on to edit several literary magazines (many of which focused on serial publications) and even publish his own literary magazine, All the Year Round, which featured many serial novels that are now famous.

A brief history of serial novels

Many of these authors (especially the early ones) wrote most, if not all, of their works in serial format. For the sake of simplicity, we just chose one work per author for our brief and oh-so-incomplete timeline of serial novels.

30 books that were originally serial novels

For those viewing on mobile, you can find the text contents of the infographic below along with links to purchase the book through Amazon.

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (1844)

- Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray (1847)

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1851)

- North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell (1854)

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1856)

- The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins (1859)

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1859)

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866)

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (1870)

- Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871)

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1875)

- The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James (1880)

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson (1881)

- Tess of D’Ubervilles by Thomas Hardy (1891)

- The War of the Worlds by HG Wells (1897)

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

- The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1901)

- The Jungle by Upton Sinclair (1905)

- The Nine-tailed Turtle by Zhang Chunfan (1906)

- The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux (1909)

- The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1910)

- Ulysses by James Joyce (1918)

- The Painted Veil by W. Somerset Maugham (1924)

- A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway (1929)

- Laughter in the Dark by Vladimir Nabokov (1932)

- Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1934)

- Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa (1935)

- And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (1939)

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote (1965)

- Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson (1971)

Limitations of serialized novels as a form

Despite the benefits of serialized publishing, the format came with a handful of disadvantages as well. Many criticisms of serial authors like Charles Dickens may actually be criticisms of the form itself, including:

- Excessively long texts

- Overly grand dramatizations

- Too much repetition

- Too many exaggerated or flat characters

- Plot lines that don’t make sense when viewed as a whole

We especially recognized this last criticism in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White.

One of the first ghost and detective novels, The Woman in White was originally serialized in 1859 in Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round. For the majority of the book, we loved it with all its dramatic, cliffhanging hallmarks of serial fiction. The end of the book, though, somehow felt both overly grand and very flat. (Without giving too much away, Collins brought in an Illuminati-esque group to explain some key plot points, a move that seemed both unexpected and false.)

Even with their well-founded criticisms, we think serial novels are worth the read, both in their original serial formats and their revised final volumes. And comparing the two versions is another fascinating story.

Modern serial publishing

These days, it seems like modern serial publishing, well, isn’t.

Though many acclaimed authors, including Zadie Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer, frequently publish single short stories or essays in magazines like The New Yorker, it’s rare for contemporary authors of traditional, heavyweight fiction to publish work as a serial novel.

Here’s a notable few authors who have recently published works in serial form:

- Tom Wolfe: The Bonfire of the Vanities (1984), published in Rolling Stone

- Stephen King: The Green Mile (1996), published as six paperback volumes

- Margaret Atwood: Positron (2012 -2013 ), self-published online

- Michael Chabon: Gentlemen of the Road (2007), published in New York Times Magazine

- Chris Ware: Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, published in Newcity newspaper

Another interesting case of psuedo-serialization today is the publication of The Martian by Andy Weir. Weir originally wrote and published chapters of The Martian on his personal blog. He gained a following of fellow space enthusiasts who helped him correct scientific inaccuracies in his draft as he went along. In the self-publishing of The Martian, Weir blended the serializing with the revising.

Future of serialization

Over the past few years, there has seemed to be a growing consensus that the serial novel is making—or is soon due to make—a comeback.

And it does seem inevitable that there will be more successful cases like Andy Weir’s as publishing moves from centralized traditional publishing houses to self-publishing, especially online. Moreover, the growth of online literary magazines and sequential publishing platforms like Wattpad will almost certainly increase the interest in and availability of serial literature, whether self-published or not.

Much like the Victorian English audience’s anticipation of Dickens’ next installment, it looks like we’ll just have to wait and see.

Leave a Reply

1 Comment on "The Serial Novel: A Brief History [Infographic]"

A lot of people, when looking at serialized novels, tend to look towards published fiction, where it usually gathers the largest audience. But while serialization in novels fell out of favor, I would argue that serialization in film (in the form of television) and serialization in drawing (in the form of comics) grew to take its place. If you look at Dickens’ criticism of serialization in books, you can see that it fits the most common criticism of long-running TV shows: repetition, a clear lack of forethought, and characters designed to momentarily grab attention (but not to hold it). As written serials have made a come back, the lessons learned from TV have been put into practice in ways that make serials stand out against most other forms of literature.

I don’t have much time for it here, but I’d like to bring up the rise of the web-serial. With platforms like Patreon democratizing payment, it’s become much more viable for authors to release work on a weekly or monthly basis. Furthermore, because Patreon handles the commitment of the regular payment, it’s more important for an author to cast a wide net for readers and provide emotional payoff than it is to keep the readers they have strung along week-to-week – once someone decides to pay an author, they have to make a conscious decision to stop paying an author. Therefore, a lot of web authors choose to publish their work for free, and focus purely on growing the size of their audience. I’ve seen the market for this sort of fiction quadruple over the last five years, and I think the trend will continue.

If you want to see what some of the more modern work in this genre looks like, I’ve posted a link below containing the top user-ranked choices for web-serials over the last several years. Not all of the things on this list are classics, but all of them are endemic to this burgeoning art style.

http://topwebfiction.com/?days=10000